Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Photographer Troy had just set up for the morning as I crested this massive dune in Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park at daybreak and had to turn back to enjoy the view.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Photographer Troy had just set up for the morning as I crested this massive dune in Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park at daybreak and had to turn back to enjoy the view.

The What

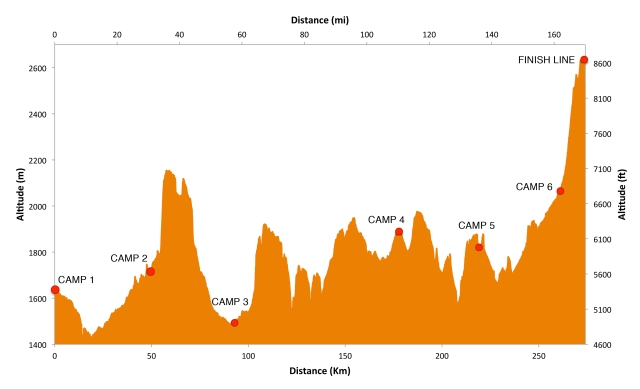

The Grand to Grand Ultra is a 171-mile stage race, divided into six stages over seven days. Runners navigate a course through the desert in Arizona and Utah from the north rim of the Grand Canyon to the top of the Grand Staircase. Grand to Grand is a self-supported race: runners carry everything they need or want for the week in backpacks. The race provides tents in a camp at the end of each stage, and water for drinking in camp and at check points along each day’s route.

The Grand to Grand Ultra is tough. Beyond tough. Perhaps the toughest of the world’s desert ultra stage races. The course winds 171 miles from the north rim of the Grand Canyon to the top of the massive Grand Staircase, through shade-less desert; rocks and cliff faces that reflect, hold, and radiate intense light and heat from all directions; steep climbs that leave no option but to suck desiccating air into your mouth and lungs like a flounder on a hot pier; trail-less routes across miles of sage brush, cactus, rocks, rattlesnakes, and scorpions; a long stage lasting into the moonless night while coyotes howl in the not-too-distant blackness; and deep, loose sand that stretches on for miles at a time.

Tough. Twenty-four percent of the field did not finish. Most DNF’d before the fourth stage. Experienced endurance athletes and ultra runners, often with at least one desert stage ultra in their legs. Ironman finishers. Extreme athletes who trained for up to a year for this specific event: long runs, runs with full packs, weight training, heat training, testing food and equipment to find the right kit and fuel that worked for them.

Beyond tough. Few of the 78 finishers emerged without at least superficial injuries. Blisters, abrasions, cuts, sunburn, cactus spines, heat rash. Or at least one day of overheating, dehydration, hunger, headache, nausea, constipation or diarrhea. Everybody hurt. Everybody, exacerbated by moments or miles or days of self-doubt, fatigue, exhaustion – physical and mental – self-criticism for a bad equipment or nutrition choice or missing a turn and going unnecessary miles before getting back on course. Experienced, extreme athletes in tears at the end of a stage that challenged them beyond the point where most people would give up. At camp in the afternoon, those who survived to run another day looked in transition from human to mummy with tape covering blisters, cuts, abrasions, and hot spots likely to get worse. Shoulders covered in tape to subdue shoulder straps that would still rub with every step of tomorrow’s stage. Heals, toes, insteps, balls of feet, tops of feet taped to cover blisters and limit further damage. Lower backs and hips taped to dampen the constant shifting and jabbing of un-padded backpacks. Knees taped to stabilize joints that fatigued muscles and tendons failed to support.

Perhaps, the toughest. Nobody thought it would be easy. Least so those who had completed other ultra stage races in other deserts and other extreme environments. They knew how the discomfort, fatigue, calorie deficit, and injuries – even if minor – accumulate and amplify day after day with no real recovery between stages. Many who had experienced the desert of Morocco or Egypt during stage ultras said Grand to Grand was tougher – harder. Sandier. Longer. The miles of soft sand exceeded the Sahara, which has more hard-packed sand. Grand to Grand is 20 miles longer than most stage ultras, which often cover 150 miles over fewer days. The opportunities for injuries and ailments increase with each day of urging the body through unforgiving conditions. Even tougher this year than most, because months without rain generated more loose sand.

Chart: Grand to Grand Ultra

Chart: Grand to Grand Ultra

Grand to Grand challenges the best, most experienced ultra runners. It challenges your physical limitations, every day. It challenges your endurance as the miles are all the harder from altitudes that drain oxygen from the air and your muscles work harder to compensate for leaner air. It challenges your strength as each stage has at least one difficult climb, miles of soft sand, and downhills steep enough that every step punishes your feet and calves and quads and glutes. It challenges your aerobic capacity and V02 max so your heart rate is all over the place but rarely in your normal zone. It challenges your mental acuity. You may miss course turns because you lapse out of mindfulness for just a moment and don’t notice the flags indicating a change in direction. You may forget items at check points as you try to move through quickly and get back on the trail. You may forget to add electrolytes to your water bottle, or consume a gel or bar, or apply sunscreen. When did you leave the last check point and how long before the cutoff to the next? How much distance have you covered since the last check point – and is it closer and faster to go back in case of emergency, or to keep going forward?

Grand to Grand challenges your will to continue. It questions your commitment, your determination, your perseverance, your grit. And if you don’t have the right answer at the right time, it will shove you off the course with no apologies. Runners come up with plenty of strategies to get through the dark periods, and many of those strategies work. Until they don’t. They are bridges to get over a point in the race when you are feeling low. They will not pull you out of the abyss of physical and mental exhaustion. You have to climb out under your own power. That’s why you have to have the answer. You have to know it in your marrow. You have to know it so well, you have to rehearse it so many times, you have to cultivate it and let it grow and flourish and develop deep roots so that when Grand to Grand rips everything else away – all the encouragement and training and planning and the reason you tell everyone else why you’re doing it – you are ready to scream back at it with a force so strong it pulls you forward in its wake.

Like the erosion that created the landscapes you run through, climb, and descend, Grand to Grand is an unrelenting process of wearing away your soft layers. It may be an avalanche like a blister that covers the entire ball of your foot. It may be subtle, like the wind carrying away one grain of sandstone at a time, or a calorie deficit that quells your hunger but cannot completely refuel you for recovery and tomorrow’s stage. Like the layers of rock that have been part of the landscape for millions of years, every part of you is vulnerable to erosion, and like those rocks, you will erode. What then? You can celebrate the resistant layers that remain. That’s the stuff that is tougher to break away, to erode. That’s where your power is. That’s what will get you through.

Without a doubt, Grand to Grand was the most fun I have ever had with a race bib pinned to my shirt. I loved the course – deep sand, steep climbs followed by what seemed like even steeper descents, miles of uninterrupted scrub, intense sun and equally intense dark night skies, the incomprehensible vastness of the Grand Canyon, the not-too-distant singing of coyotes along the trail in the middle of the night. I loved the people – my tent mates who intuitively knew how to add just the right humor or gravity to every situation, the people I talked with as we navigated the course (and sometimes backtracked to find the course), the volunteers who seemed never depleted of energy and enthusiasm, the race directors and core staff who created and managed this roving desert amoeba of people and equipment. I arrived at Grand to Grand with a good friend of 30 years: I left Grand to Grand with scores of friendships I know will last as long as the sun shines on the desert sand.

The Who

Tent 11: Papago

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. L to R: Jo (GBR), Ruby (AUS), Sarah (USA), me, Julie (USA), Frank (USA), Joe (USA). At Camp One at the north rim of the Grand Canyon on race-eve, all clean and buzzing with nervous energy. Frank and I worked together in the early ‘90s. He’s the only person I knew before Grand to Grand.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. L to R: Jo (GBR), Ruby (AUS), Sarah (USA), me, Julie (USA), Frank (USA), Joe (USA). At Camp One at the north rim of the Grand Canyon on race-eve, all clean and buzzing with nervous energy. Frank and I worked together in the early ‘90s. He’s the only person I knew before Grand to Grand.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. With race directors Tess and Colin Geddes front and center (in western hats), 102 adventuresome souls stand at the edge of the Grand Canyon, ready to begin our 171-mile, 7-day odyssey through the desert. I’m under the flag of Spain, in white, long sleeves.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. With race directors Tess and Colin Geddes front and center (in western hats), 102 adventuresome souls stand at the edge of the Grand Canyon, ready to begin our 171-mile, 7-day odyssey through the desert. I’m under the flag of Spain, in white, long sleeves.

You may think an ultramarathon is an individual sport. In many respects, you’re right. Everyone has to carry their own food and equipment, with stiff time penalties for carrying items for another runner or giving them food or equipment you don’t want (a practice called “muling”). Everyone has to get through each stage and to the finish line under their own power. But this is very much a social sport and event. Tentmates can become quick intimates, sharing fears, frustrations, and pains…the real reasons they are here and not the surface reasons people back home might better understand…the little victories like emerging unscathed after pooping in a field of cactus and sagebrush in the middle of the night…moments of encouragement and support on the trail in the heat of the day…juvenile puns and hilarious observations…. I am happy to say I enjoyed the company of these tentmates throughout the week. And we all made it – 100 percent finishers from Papago!

The 2019 edition of Grand to Grand started with 102 participants from 22 countries. Over the week I shared trail and camp time with people from every continent except South America. People from countries or regions in turmoil – such as Hong Kong, the UK, and the US – glad to be away from the news but a little nervous about what might be happening while they were away. Fathers about my age with sons about the ages of my sons, dealing with similar and divergent issues. Americans on both sides of our country’s growing political wall. Brits on both sides of Brexit. People from other EU-member countries with their own thoughts on Brexit. Kiwis who wonder why the US can’t take the same decisive action to protect its citizens that New Zealand did after its own recent gun massacre. Beyond the politics, we were – are – all pretty much the same: people willing to push ourselves beyond the comfort zone to accomplish something most people think impossible. To prove that impossible is mostly a state of mind, a self-imposed limitation. An excuse. A taunt.

The Why

I discovered endurance pursuits in my late 30s, when I found myself exhausted from playing with my preschooler for 20 minutes. I was overweight, out of shape, and riding a couch toward the deep end of middle age with a remote control in one hand and a bottle of wine in the other. I started riding a bike. Then I did a 300-mile bike tour of Newfoundland. Then I watched a sprint triathlon and decided competition would bring more motivation. A decade of triathlon life – including seven Ironman finishes – and road marathons turned me from pudgy to lean and from a spectator to participant and sometimes-competitor.

I turned toward trail running after getting burned out on all the technical aspects of triathlon – which bike and which wheels were best for a given course, obsessing over my swim form to minimize drag and optimize efficiency, bike metrics (cadence, power, gear ratios). Too many close calls with SUVs driven by distracted or uncaring drivers on narrow country roads and on the shoulders of busy urban and suburban roads squashed my faith in the notion of sharing the road. Too many Type-A guys out to establish their manhood by swimming on top of people, riding peloton-style throughout the bike course, and numerous other unsafe and illegal ways to get an edge they didn’t earn.

What to do with all that fitness and the need to maintain it without Ironman? Trail ultras, of course. But why stop at running a long way on a trail if you can run insanely long over a week in remote desert with no creature comforts? Now we’re talking!

The When and Where

Camp 1, night before start.

Journal entry: Drove/rode to Camp One at north rim of Grand Canyon. Time to relax, sit on rim, took a nap in tent, got to know tent-mates a bit. Dinner at long banquet tables overlooking canyon. Got chilly quickly as sun went down; campfire. Wildfire on the horizon with large plume of smoke – wind blowing in favorable direction. I’m feeling fairly relaxed – we’re here – all options and decisions are done or no longer options. Tomorrow’s stage is 30+ miles and I’m just ready to start, get in the groove, and go until the end – just like training and other races.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Truth in marketing, literally starting at the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Truth in marketing, literally starting at the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Stage 1: 30.8 miles; 1,653 feet ascending; 1,358 feet descending.

My results: 9:36:33 (that’s 9 hours, 36 minutes, 33 seconds), 74th of 102 overall, 53rd of 67 males

Risks: “This area has dense vegetation with a lot of cacti. Their spines go through your shoes very easily getting deep into your skin. It is recommended that you wear protection and keep your eyes constantly on the ground in front of you.” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal entry: Awakened at 06:00 by Reveille, followed by high energy pop music from the 70s to present from the loudspeaker. Breakfast, oatmeal. Started near rim of Grand Canyon. Check Point One was back at rim, then away into the desert. Saw lizards, also coyote and antelope scat. Condor “white wash” below roosts on Vermillion Cliffs near Camp 2. Ran to Check Points One and Two, walking hills. Then intense sun and heat got strong. Was going to run flat sections still, but saw everyone in front of me walking. Then I got a little dehydrated, hotter, and kept walking. As always, I passed people who had passed me earlier. Chatted with plenty of people in short bits throughout the day. Got to camp, had black bean soup right away, more water, hot chocolate, water. Had headache since middle of last night and throughout the day – is finally gone. Got a small blister on inside of each heel, but no other blisters or abrasions from gear. Half our tent came in within about a half hour of each other – no dropouts or real injuries today. Frank about an hour ahead of me today.

Mental diversion: Sang the entire album of Quadrophenia.

Highlights from mail (supporters could send messages via the race website, which were printed at distributed to each tent after each stage):

- “May this turn into a tattoo worthy adventure of your body, mind, and spirit.” – Alice and Richard

- “Anticipate exciting moments and sights.” – Mom

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. In daylight, the bright pink flags and ribbons showed the way, as long as we paid attention. At night, reflective stickers and LEDs on the flags were to runners what the North Star is to sailors. Despite the well-marked course, I took a few wrong turns and had to backtrack.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. In daylight, the bright pink flags and ribbons showed the way, as long as we paid attention. At night, reflective stickers and LEDs on the flags were to runners what the North Star is to sailors. Despite the well-marked course, I took a few wrong turns and had to backtrack.

Stage 2: 26.9 miles; 2,355 feet ascending; 3,044 feet descending. 8 DNFs.

My results: 9:17:55, 70th of 94 overall, 48th of 61 males.

Risks: “The course leaves the main trail and turns right. It is easy to get lost. Make sure to always follow the pink course markings!” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal entry: Started with brief climb, then long steep climb, plateau with nice cool breeze and amazing views. Then steep downhill with views and a new blister on left little toe. Shoulders very sore from weight of pack – no blisters there but very sore. Seven DNFs today. Big burrows – badgers? This is hard work: 50K/30 miles yesterday then a marathon today. Feet hurt. Hip flexors hurt more than anything. Shoulders hurt. This is what ultra is – learning to accept the pain and discomfort and keep moving forward. Keep going in spite of it all – the challenges, doubts, fear, self-criticism. Trying to stick to nutrition and hydration plan during the day, on the move. Did well today but got dehydrated in yesterday’s heat.

Mind diversion: Sang the entire album and soundtrack(s) of Tommy, switching frequently from album version to movie version to Broadway version. Included the one song Pete added for Broadway. Which I hate.

Highlights from mail:

- “I checked the site but there are no updates yet. But I have not gotten an emergency phone call so that’s good news.” – Nancy

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Note the group of runners to the lower left of the dark green junipers. The vastness of the landscape is both overwhelming and grounding.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Note the group of runners to the lower left of the dark green junipers. The vastness of the landscape is both overwhelming and grounding.

Stage 3: 53.2 miles; 5,570 feet ascending; 4,278 feet descending. 15 DNFs.

My stats: 28:30:31, 66th of 79 overall, 42nd of 51 males.

Risks: “Cross country, sandy and thick vegetation. Slow to navigate, especially at night.” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal entry: Heard group of coyotes in the distance – but not too distant – on long, straight road before Check Point Six. Moonless sky was dark and brilliant. Spoke/walked with several people who never/rarely see Milky Way but definitely got a good view here. Wow, this stage was a serious test of will. Fifty-three miles after 30 and 26 the days before. Deep sand to manage most of the way made slow going even slower. Was not as hot the first afternoon, but the second morning and afternoon were really hot with little wind. Like so hot I was taking breaks in the shade of trees. Took my time in check points. Tried to stay in low gear. Just before dark I was with guys from Jar of Hope, Joe from my tent, Michael from New Zealand, and rotating others as they caught up or fell back. Staying with Joe and Michael until Check Point Six at 1:30 a.m., then I slept for about three hours and they moved on after two. Got to the dunes with Kay just before sunrise. Got hot quickly with sun. Caught up with Joe and Michael, Paul from Wales, and others at Check Point Seven. Joe was struggling from heat, dehydration, etc. Paul was enjoying a “food sauna” to treat blisters and raw flesh.

Highlights from mail:

- “You are physically fit and have the strength to do just what you’ve set out to do.” – Mom

- “Well your number is still listed, so I guess you’re still alive and kicking.” – Nancy

- “Please remember to use all the dried food and not bring any home with you.” – Ben

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Gaiters covering the entire shoe upper were essential to keep out abrasive sand.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Gaiters covering the entire shoe upper were essential to keep out abrasive sand.

Stage 4: 26.0 miles; 2,926 feet ascending; 3,182 feet descending. 1 DNF.

My results: 10:18:28, 71st of 78 overall, 45th of 51 males.

Risks: “The last 10 kms of this stage are difficult. Uphill and soft sand. Save your energy for this leg.” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal Entry: Today was most comfortable day so far. Intermittent clouds and cooler temps, but I think the biggest factor was the psychological boost from completing the long stage with plenty of time to spare, and the length of the long stage. Today was “only” a marathon! Had to get up to pee at 3:00 a.m. – the first night since we left Kanab. Think I finally got my hydration figured out. Michael and I came upon L, who was in a sleeping bag in the shade of a tree just off the trail. We asked if L was OK and L said yes and that we could go on. Asked if L had everything or needed anything – L said yes and no, but the situation didn’t feel right to me. I sat down and started assessing while Michael went on to the next check point to make sure the docs knew. L was conscious and lucid: L knew their name, where they were, and was concerned that I would lose time if I stayed with them. L said they had not been able to keep food down and was shivering uncontrollably, which explains the sleeping bag. L asked me to hold their hand and I was surprised at how cool it was – a classic sign of heat illness (we used to call it heat exhaustion, which can lead quickly to life threatening heat stroke). I stayed with L about 30 minutes until Doc Josh arrived – he humped it about two miles from Check Point Four on the sandy road with his medical kit/backpack. Josh assured me he was OK on his own so I returned to the trail and headed on my way, a little behind on time but very glad I was able to be there.

Highlights from mail:

- “Your drive, your determination and your passion are truly inspiring.” – David

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Photographer Barry knew just when to shoot to make it look like I was flying over this tree trunk. In truth, I was doing my best to gingerly hobble over it on tired, tight legs.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. Photographer Barry knew just when to shoot to make it look like I was flying over this tree trunk. In truth, I was doing my best to gingerly hobble over it on tired, tight legs.

Stage 5: 26.5 miles; 2,929 feet ascending; 2,093 feet descending. 0 DNFs.

My results: 10:05:13, 69th of 78 overall, 46th of 51 males.

Risks: “There are several places in the slot canyon which will require you to drop down over boulders. You will be able to navigate some of these on your own but there are others which will require the assistance of ladders and volunteers for a safe descent.” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal entry: Forgot both water bottles at Check Point Two – realized it 20 minutes later when I reached for a drink. Went back about ¾ mile to get them. Check Point was already closed and sweepers had bottles. At that point I was DFL. I put it in gear to make up time. Ended up passing 11 people including Tigger and Joe. Not bad after 35-minute round trip to get the bottles.

Mind diversion: None. Just focused on keeping it in gear and staying on course.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. The view from the finish line. We started Stage One at about 5,400 feet above sea level in desert scrub and finished Stage Six at about 8,700 feet in Piñon Pine forest.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra. The view from the finish line. We started Stage One at about 5,400 feet above sea level in desert scrub and finished Stage Six at about 8,700 feet in Piñon Pine forest.

Stage 6: 7.7 miles; 2,742 feet ascending; 869 feet descending. 0 DNFs.

My results: 2:28:38, 59th of 78 overall, 42nd of 51 males.

Risks: “The Grand View Trail is an easy trail to follow. However it can get very narrow at some points. Please be cautious, in case of land slips.” ⁓ Grand to Grand 2019 Course Book

Journal entry: Final stage was all uphill. Mostly gradual. The morning started cool and cloudy – I started with my shell and kept it on throughout to the finish line. Required to keep silent the first 5K because the course passed through a mule deer migration pathway – they’re apparently threatened here. As we rose above desert we got into some golden-leaved Aspen in the creek bed, then bright reds, then Piñon Pines. Clouds thinned and could see pink cliffs above. Flattened out at a parking lot, then an easy climb up the final mile to finish line. Very chilly and windy at top after finish. Donned puffy jacket, tights, and sleeping bag as a cloak to keep warm. Five pieces of veggie pizza, second Coke of the week. Cheered in many other runners. Plenty of tears from runners – releasing months of stress, anticipation, effort, perseverance, pain, fear, joy, accomplishment, elation.

Total: 171.1 miles; feet 18,175 ascending; 14,824 feet descending. 24 DNFs.

My results: 70:17:18, 68th of 78 overall, 45th of 51 males, 15th of 16 Males 50-59.

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra

At the finish line with Tess and Colin Geddes, co-Founders and Directors of Grand to Grand. They were there every step of the way. They saw us off each morning at the day’s start line. They showed up with encouragement at unexpected moments along the course. They welcomed us to the finish line each day with hugs and smiles.

The How

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra

Photo: Grand to Grand Ultra

Gear

All that stuff on the bed (left) actually fit inside my 24-Liter pack, seen (right) during Stage One, total weight at start about 19 pounds with full water bottles. Starting at top, right on bed: red sleeping bag (required to be rated down to 30 degrees F), yellow sleeping pad below blue backpack, dark gray insulated ultra light coat and dark gray ultra light rain jacket, running hat and buff, two sets running clothes (shirt, shorts, compression socks), long/warm camp clothes and socks, water bottles (required to have 1.5 Liter capacity), running shoes with Velcro sewn above the soles to attach sand-blocking gaiters, gaiters in front of shoes, running/hiking poles, sunscreen, toilet paper for day use along the trail, flipflops for camp, and all that little stuff in the middle (two headlamps, extra batteries, compass, signal mirror, red tail light for night running, emergency mylar blanket, blister prevention and care kit, titanium mug and spork, ear plugs (for communal tents where everyone snores).

How the key gear worked out

Backpack: The Raidlight Responsiv 24-Liter Vest was not my first choice. I started training with a used Ultimate Direction 25-Liter fastpack, which has a little more structure. After several training runs, I couldn’t get the UD fit right. The straps kept rubbing my clavicles raw. I switched to the Responsiv because it was lighter (at 10.2 ounces) than the UD (at 19 ounces, that’s an extra half-pound to carry). The Responsiv fit all my gear with some room to spare – I loaded everything into the main compartment and outer pockets. The pack has loops and cords for attaching more gear, but I didn’t need them. The only problem with this pack is the “Lateral Micro Adjust System”: a dial and monofilament linking two plastic struts at the point where the shoulder straps join the bottom of the pack. One of the struts is inexplicably longer than the other and has a bad habit of digging into one’s lower back and upper hip if the gear is not loaded just right, inside. I discovered this flaw during training and found that when I loaded the pack just so, the strut stayed away from my back. Still, early in Stage One, I felt the familiar hot spot developing, so with the help of a volunteer at Check Point Two, I put some KT tape at that point and moved on. I had no other problems throughout the week. One of my tent mates, Sarah Lavender Smith (who finished top female and 10th overall), had a more serious problem with her Responsiv: during Stage One, the monofilament broke on one side, leaving the pack to bounce and sway for the rest of the stage. She did a field-fix that night by cannibalizing the drawstring from her shorts, which held through the rest of the stages.

Sleeping bag: Last winter, I bought a Mountain Hardware Phantom Spark 28F on closeout. I learned while gearing up in my early triathlon days: this year’s closeout section is filled with last year’s state-of-the-art gear. I bought my bag in the winter so I could test it during cold weather – Grand to Grand temperatures can drop below freezing and I’m a cold sleeper, so I wanted to make sure I got this right. I don’t think our nights on the trail fell to freezing, but I was comfortably warm every night in my skivvies. In a fit of weight reducing panic, I cut the compression straps and buckles off the stuff sack. The stuff sack was small enough to fit in my pack and every ounce removed is an ounce not weighing on my shoulders.

Sleeping pad: Looking at the options – closed cell foam pads that only fit on the outside of the pack, or inflatables that fit inside – I went with the Thermarest NeoAir XLight. The pad is inflatable for that just-right firmness and rolls up smaller than a water bottle to fit inside my pack. Thanks to a tip from a tent-mate, I slept with the pad inside my sleeping bag to reduce the risk of punctures. At one campsite which seemed virtually carpeted with goat heads, we also spread our mylar emergency blankets under our bags as another barrier to punctures.

Shoes and gaiters: My go-to trail shoes are Salomon Speedcross 4, which I trained in through June. Then I started thinking about the pounding, day after day, deciding something with more cushion might be a good idea. Hoka One One Bondi’s are my favorite road shoe for long training runs on hard surfaces, so I went with the Hoka Stinson, a cushiony shoe with a not-too-aggressive sole. For gaiters, I went with the Raidlight Desert Gaiters. To sew the gaiter Velcro to the shoes, I took the shoes and gaiters to the cobbler who has worked magic with all types of my work and play shoes for years. He had not seen desert gaiters before but was willing to give it his best – I trusted him. After a few training runs with his handiwork, I realized I needed to redo the Velcro job. I then hand-sewed the Velcro to the Stinsons and instantly saw the difference between knowing shoes and knowing how sand gaiters had to work. After Stage Four, I noticed a section on the first shoe I sewed was starting to separate, but not much. At the end of Stage Six, everything was still in place and the gaiters kept the sand at bay. They kept the sand out – but not the dust – pulverized sand, reduced to dust, gets everywhere, but is much less abrasive than full-sized grains of sand.

Flip-flops: There are two schools of thought on footwear for camp. One: just take the insoles out of your running shoes for walking around camp and leave the extra weight of flip-flops at home. Two: take the flip-flops so your feet can breathe and get away from the parts of your running shoes that may be causing problems. I swung back and forth on this decision until the night before we left for the Grand Canyon. Decided to take the weight with me. And glad I did – so much more comfortable around camp than the shoes I had been pounding all day. I had the added bonus of taking the flip-flops I picked up for 12 Sol at a tiny trail-side mercado in the Peruvian highlands last summer.

Food

Each competitor is required to carry a minimum of 2,000 calories per day, with a minimum weight of 7.7 pounds at the beginning of Stage One. L to R, front to back: dried apple, mango, banana snacks, Generation UCAN bar snacks, soups (black bean, potato, corn chowdah, each w/olive oil and TVP) suppers, oatmeal (w/almond butter, powdered milk, brown sugar, salt, cinnamon) breakfasts, Generation UCAN energy drinks chocolate & vanilla during day, hot dark chocolate with powdered milk for bedtime, Generation UCAN hydration/electrolyte mix during day, Starbucks Via for caffeine whenever, extra olive oil & almond butter just in case. Average 2,505 calories per day. Total weight 8.6 pounds.

Because just training for Grand to Grand wasn’t enough, I took on the additional challenge of making as much of my own food as possible. I got a food dehydrator. I experimented with ingredients and recipes. I studied USDA nutrition information for each ingredient. In the end, I came up with mixes of oatmeal for breakfast and soups for supper with sufficient calories, carbohydrates, fat, and protein for refueling, anti-inflammatory properties, and whatever recovery was possible overnight. I found dried apples, mangos, and bananas to be high in calories/carbs and low in weight. Plus I liked them, which helped get them down during hot afternoons on the move.

I ate most of what I took. Throughout the week, I felt well fueled, never close to bonking. After Stage Three – the long stage – I surrendered what I thought I could live without while not dropping below the required food weight for the remaining stages. I gave my extra almond butter packets, one oatmeal bag, and a couple of UCAN bars to Garth Reader, the Race Commissioner. Turns out I was just under the required weight when Garth checked my food after Stage Four, but not enough to warrant a time penalty.

What I would do differently

- Spend a lot more time hiking with a full pack. I spent a lot more time hiking than I had expected. I spent a lot more time hiking than running. Feet and shoes interact differently when hiking than running – that’s probably a factor in my blisters.

- Spend a lot more time on soft sand. The course had a lot of soft sand. Like the dry sand above the high tide line on a mid-Atlantic beach soft. There’s nothing to grip, just sand to sink into until your foot rocks forward with your body momentum.

- Add more spice to my meals – especially salt. I had plenty of salt and other electrolytes throughout the day and in my morning and evening meals, but I found myself wanting more salt with my suppers. I might add half-packets of ramen noodles to my supper plans, next time. Not much nutrition there, but easy to eat and drink quick carbs and salt.

- Be less conservative with my pace and energy. This was my first stage race and I wanted to respect the distance and the challenge, so my primary goal was to go easy and survive to the finish. In retrospect, I think I could have gone harder each day – run more each day, burn more fuel each day. Now that I have been through a stage race, I think I can survive with less reserve.

What I learned from other participants

- When the veterans say go with gaiters that cover the entire shoe and must be attached by sewing at the sole, do that. One tentmate, whom I shall call Revenant, found out that the guy at REI may know that Salomon gaiters go well with Salomon trail shoes, but unless he knows running in deep sand, his opinion means squat. During Stage Two I saw a person who had simply used the adhesive that came with the Velcro to stick to the shoe – the Velcro was mostly not sticking and the gaiters were virtually useless. I saw duct tape used to cover areas of shoes not protected by standard trail gaiters. I saw feet in plastic bags inside shoes because the sand was pouring in. Get the full-shoe sand gaiters. Get them. Seriously.

- When you start at your normal pace, you finish in trouble. The fittest runners had their paces dialed in and ran as they knew they could. Many of the other runners – especially some middle-aged guys – started Stage One at the pace they might take a normal training run, getting caught up in the excitement. Some of them managed that pace just fine. Others fell back, and fell farther back each day.

- No matter what, keep moving forward. Pain happens. Discomfort happens. Blisters, scrapes, sunburn, heat rash, hunger, thirst, taking a wrong turn, being DFL – it all happens. Barring race-ending injury or illness, if you keep moving forward (in the right direction), you will make it to the finish line.

- There is a wide, fuzzy zone between pushing past your limits and risking your life or permanent injury. Get comfortable in that zone but be ready to accept reality when you pass into the clear danger zone. The person I sat with who was experiencing heat illness stopped while still lucid enough to leave their pack on the trail (so other runners and the “sweepers” – the volunteers who follow the last runner to make sure everyone gets to camp – would know they were nearby), move into the shade with sleeping bag and water bottles, and describe their symptoms. Had they kept going in that condition, they may have gone into heat stroke and lost consciousness in full sun and spiraled downward quickly.

Tips for first-timers

- Ask a lot of questions – especially the stupid questions. Find veterans of this and other ultra stage races. This is what Facebook was invented for, after all. Ask what equipment they used, what food they used, how they stayed dry or warm or not too hot. Ask how they trained. Ask what they did not take that they wished that had. Ask what they took that they wish they hadn’t. Ask everything. Don’t blindly do what others say they did, but take it into consideration and decide what works for you.

- Read race reports. Search them out and read them. All of them. Learn about how the course challenged the lead runners and the back of the packers. Learn what you can look forward to and what you will have to cowboy up for. Race reports can dispel some of your fears and they can give you new concerns to start working on. Don’t blindly do what others say they did, but take it into consideration and decide what works for you.

- Buy gear early and test often – you will change some of it. It’s an expensive way to find out what works best for you, but it’s better to spend the money than to suffer from a pack or sleeping bag that doesn’t work for you.

- Read “The Trail Runner’s Companion: A Step-by-Step Guide to Trail Running and Racing from 5Ks to Ultras,” by Sarah Lavender Smith. Sarah is the 2019 Grand to Grand Women’s Champion and overall Top-10 finisher. Even if you’re an experienced runner but first-time stage racer, this book will help you understand the unique training needs of multi-day events. Her approach is conversational and uncomplicated, making her sage advice understandable, even to me.

- Read “Fixing Your Feet: Injury Prevention and Treatments for Athletes,” by Jon Vonhof, sooner than later. After months of seeing posts about this book, I finally got it four weeks out from Grand to Grand. Did it change my equipment or strategy? Not really, but it gave me a lot more information about preventing and minimizing the damage of blisters and other foot problems, and it did influence a couple of additional small purchases for my required blister kit. If you have injury-prone feet, this book just may keep you in the race.

- Know how to use all your required emergency gear before you need it. Getting lost on a moonless night in the middle of the desert is no joke. Getting lost in the middle of the desert in the heat of the day is no joke, either. You’re required to have a compass: know how to use it with the map in the race guide so you don’t get more lost. Same for that required signal mirror.

- Know basic first aid. You or another runner may get injured or succumb to heat illness between check points with the race medical team an hour or more away and transport to a hospital even longer down the line.